Researchers at Dartmouth College have identified a region of the human brain that seems to predict a person's self-esteem levels.

It's called the frontostriatal pathway, and the stronger and more active it is in the brain, the more self-esteem someone has. The findings, published online in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, could help change the way we understand self-esteem: not as a panacea for all problems, but as a physical indicator of risk for psychological disorders.

"People think raising self-esteem will raise IQs and test scores, and that hasn't really panned out," said lead author Robert Chavez, a Ph.D. student at Dartmouth. "We should be looking at it more as a measure of how susceptible you are to psychopathologies like depression and anxiety."

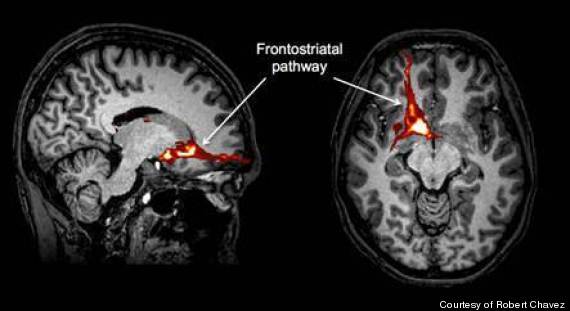

Chavez found that self-esteem lies in the frontostriatal pathway, highlighted in the illustration below:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A depiction of the anatomical connections between the ventral striatum and the prefrontal cortex. The strength of these connections correlated with subjects' self-esteem scores in the study. (Courtesy of Robert Chavez)

It connects the medial prefrontal cortex, which deals with self-knowledge, to the ventral striatum, which deals with feelings of motivation and reward. Chavez used two different kinds of magnetic resonance imaging to measure both the physical boundaries of the pathway -- what he called the "road" -- and activity levels on that pathway -- or the "traffic" on that road.

If a person had a very strong "road," he or she was more likely to have higher long-term self-esteem. The "traffic" levels on that road, however, predicted higher momentary self-esteem.

Sometimes a person's frontostriatal pathway would be both anatomically strong and very active, but one quality didn't necessarily lead to the other.

For the study, Chavez and Todd Heatherton, Ph.D., a Dartmouth professor, teamed up to scan 48 people's brains using both diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). While the scans were taking place, participants answered questions about how they saw themselves in the moment and long-term by rating themselves on qualities like "hard-working," "happy," "depressed" and "pessimistic." The terms were equally split between positive and negative descriptions.

Then Chavez analyzed participants' brain scans and matched them up to the times they rated themselves based on certain traits. He saw that when participants answered about self-esteem in the short term, the scan showed a lot of activity on the pathway. Meanwhile, the stronger the pathway was anatomically, the more likely participants were to have long-term self-esteem. Interestingly, Chavez only saw brain activity on the scans when people rated themselves with positive terms, not negative ones.

"Being down on yourself doesn't drive these effects," explained Chavez. "It's more driven by the positive aspects of your sense of self."

Given past studies about how repeated behaviors (say, meditation) can actually alter brain traits, Chavez is hopeful that researchers can figure out a way to change or strengthen the frontostriatal pathway with therapy -- and use MRIs to monitor a patient's progress.

It's called the frontostriatal pathway, and the stronger and more active it is in the brain, the more self-esteem someone has. The findings, published online in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, could help change the way we understand self-esteem: not as a panacea for all problems, but as a physical indicator of risk for psychological disorders.

"People think raising self-esteem will raise IQs and test scores, and that hasn't really panned out," said lead author Robert Chavez, a Ph.D. student at Dartmouth. "We should be looking at it more as a measure of how susceptible you are to psychopathologies like depression and anxiety."

Chavez found that self-esteem lies in the frontostriatal pathway, highlighted in the illustration below:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

A depiction of the anatomical connections between the ventral striatum and the prefrontal cortex. The strength of these connections correlated with subjects' self-esteem scores in the study. (Courtesy of Robert Chavez)

It connects the medial prefrontal cortex, which deals with self-knowledge, to the ventral striatum, which deals with feelings of motivation and reward. Chavez used two different kinds of magnetic resonance imaging to measure both the physical boundaries of the pathway -- what he called the "road" -- and activity levels on that pathway -- or the "traffic" on that road.

If a person had a very strong "road," he or she was more likely to have higher long-term self-esteem. The "traffic" levels on that road, however, predicted higher momentary self-esteem.

Sometimes a person's frontostriatal pathway would be both anatomically strong and very active, but one quality didn't necessarily lead to the other.

For the study, Chavez and Todd Heatherton, Ph.D., a Dartmouth professor, teamed up to scan 48 people's brains using both diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). While the scans were taking place, participants answered questions about how they saw themselves in the moment and long-term by rating themselves on qualities like "hard-working," "happy," "depressed" and "pessimistic." The terms were equally split between positive and negative descriptions.

Then Chavez analyzed participants' brain scans and matched them up to the times they rated themselves based on certain traits. He saw that when participants answered about self-esteem in the short term, the scan showed a lot of activity on the pathway. Meanwhile, the stronger the pathway was anatomically, the more likely participants were to have long-term self-esteem. Interestingly, Chavez only saw brain activity on the scans when people rated themselves with positive terms, not negative ones.

"Being down on yourself doesn't drive these effects," explained Chavez. "It's more driven by the positive aspects of your sense of self."

Given past studies about how repeated behaviors (say, meditation) can actually alter brain traits, Chavez is hopeful that researchers can figure out a way to change or strengthen the frontostriatal pathway with therapy -- and use MRIs to monitor a patient's progress.